Child Abuse and the Brain

There's no doubt that child abuse has serious consequences. The effects, however, may be even worse than you think. An increasing amount of research indicates that severe maltreatment at an early age can create an enduring negative influence on a child's developing brain. The findings highlight the seriousness of childhood abuse and may lead to increased prevention efforts as well as new approaches for treatment.

A twisted arm. No food. Rape. It's heartbreaking to think about. Almost 900,000 children faced some form of abuse or neglect in 2000, according to the most recent data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Clearly these actions have serious consequences, but the extent and nature of the effects were unclear. Now, an increasing amount of research indicates, that while physical wounds often heal over time, severe maltreatment at an early age can create an enduring, harmful influence on a child's developing brain. The research is leading to:

A better understanding of how negative environments affect the brain.

Increased efforts to intervene and protect children from maltreatment.

New ways to treat abuse.

As children sprout in stature over the years, so do their brains. The cells and circuits build and refine. Researchers recently began to suspect that maltreatment might throw a stick in the gear of this sensitive time of growth and cause problems. Although still in an early stage, when looked at altogether, several lines of study support this theory.

For starters, evidence indicates that many maltreated children end up with mental ailments. They appear more likely than healthy individuals to experience learning problems, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a condition marked by intense anxiety that sometimes erupts after a horrific experience, according to some studies.

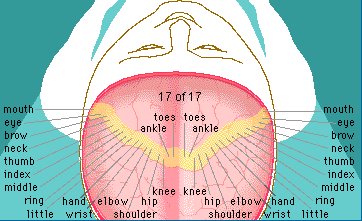

Maltreatment also may affect brain anatomy. Compared with healthy individuals who never experienced abuse, some brain areas are smaller in those who experienced maltreatment and have PTSD (see illustration). It's possible that maltreated kids are born with the smaller structures, but many scientists suspect that the finding signals that abuse harms brain development. And these developmental issues may help spur the disorders common in abused and neglected children.

At the root of these problems may be the stress associated with maltreatment. When we experience a stressful situation, our brain's stress system activates a slew of biological actions. This helpful response prepares our body to fight or flee. However, perpetual or intense stress, especially during the brain's sensitive development time in childhood, may harm this system.

In fact, research that measures various stress molecules finds that sometimes they are out of whack in maltreated children and adult survivors. In another example, young rodents separated from their moms for a few hours each day, a source of significant stress, show signs that as adults their stress system does not work properly.

The altered stress system may trigger other problems. Extremely stressful situations appear to cause brain cell death in rodents and may do so in humans as well. In addition, infant monkeys raised individually have a smaller corpus callosum. This collection of fibers that connects the two halves of the brain also was found to be smaller in some maltreated children.

Recently researchers discovered a group of monkeys that will help them better test the effects of stress in child abuse. The mothers naturally act abusive to their offspring. Early findings indicate that the bad parenting alters the stress systems of the abused. Plans to examine brain anatomy are under way.

On the positive side, researchers also are examining maltreated children who do not seem to suffer from mental ailments and function fine in life. They want to know if a person's genetic makeup, a teacher's support or other factors could play a role.

In addition, investigators are testing ways to block or reverse abuse-related biological alterations. For example, early findings indicate that some medications used for depression can reverse problems with the stress system in rats raised in stressful environments and may aid abused children.

Of course, researchers say that the best solution is to prevent maltreatment from occurring in the first place.

Some research shows that maltreatment may affect brain anatomy. For example, in one study researchers examined the brains of maltreated children and adolescents with PTSD. Compared with healthy individuals who never experienced abuse, those who were maltreated have smaller brain areas. Included is the cerebral cortex and prefrontal cortex, which help carry out complex actions; the corpus callosum, which helps the two sides of the brain communicate; as well as the temporal lobes and the amygdala, areas thought to be involved with emotion and memory. Research also finds that a memory area, the hippocampus, is smaller in adult survivors of abuse with PTSD. Although still under investigation, it's possible that experiencing maltreatment during youth harms overall brain development and helps spur the ailments that seem to be common in these individuals.

Illustration by Lydia Kibiuk, copyright © 2003 Lydia Kibiuk.

Sunday, July 1, 2007

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

http://www.windyweb.com/stop.htm

No comments:

Post a Comment